Brick and tile making in Yardley

The standard work on early Yardley is Victor Skipp’s Medieval Yardley. This is an extract from chapter 19: Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Century Crafts, with associated references.

Tile-making collects its first documentary references at the beginning of the fifteenth century. We hear of William Tyler in 1402, Amisia Tyler in 1420, and of Robert Robyns, tyler in 1463.(1) In the mid-nineteenth century the main concentration of tileries was along the Coventry Road, and northwards from this to Yardley village - including four in the village itself (see map facing page 26).(2) Probably the same area was the centre of the medieval industry. However, a deed of 1497 refers to a Kelyn crofte and Kelyn mede at Stechford,(3) while in the south of the manor Tittiford has a Tylehowse Place (alias Pretties Place) by 1588, and in 1612/13 there are two closes at Sarehole called Tilehouse Crofts.(4)

The clay preferred for tile making was a plain red clay, and Yardley's, according to Nash, was 'of particularly good quality which if properly tempered and burnt will last longer than the memory of man.'(5) From the O.S. Geological map, it would appear that the seventeen known kiln sites were almost invariably situated on the Keuper marl. But since sand had to be mixed with the clay before firing, the sites chosen - except in three instances - were close to a drift deposit. In fact they are often on a marl-sand or marl-mixed drift junction. The earliest tile-makers quite likely quarried the marl from clay pits, but sooner or later layer excavation became the rule. In 1715 when James Hopkins, yeoman, acquired two closes called Bowling Green Lesowes at Yardley village he was given free liberty 'to dig or get Clay...levelling the Ground again after the getting thereof and also laying upermost after the getting of the Clay, the soil first dug off before the getting...(6) This procedure may account for the fact that fieldwork has failed to reveal any clear evidence of quarrying activity at the kiln sites.

Probate inventories provide the names of several sixteenth-century tile-makers and also offer some insight into the mysteries of their craft. Thomas Walton who died in 1554 had a Nether and an Over 'tile howse'.(7) The kiln which was apparently in, or built on to, the latter was loaded when the inventory was taken:

tile in the oven not ealled (not fired) 5 thousand, 5 thousand and a half of Brycke and 12 dossen gutters (convex tiles used for drains or gutters), 5 dossen quarrekes (quarries, floor-tiles), 4 dossen Crestes (coping tiles for the ridge of a roof).

It was customary, as here, to fire tiles and bricks together. The tiles tended to warp if exposed to too much heat, so banks of bricks were built up to shield them. In both his tile-houses Thomas Walton had unfired material ready to be put into the oven: in the Nether house 'tile & brycke not ealed by estymacion 3 thousand', in the Over house 'tyle...not ealed 2 thousand & gutters 10 dossen.' Altogether there were 15,372 pieces of unfired tilery which the appraisers valued at 32s. 8d. 'Tile ealed 4½ thousand' at the Nether house, on the other hand, were priced at 33s. 4d. In Tudor times kilns were still being heated with wood and 'kyddes' - sticks, furze, etc. At the Nether house there was 'Wood & kyddes by estymacion 50s.', at the Over house 'Wood by estymacion 26s. 8d.' This last item may not have been firewood though, for Thomas Walton practised coopery as a second craft. 'In the yarde' he left 'Cowpers tymber 4½ thousand staves 4 hundred bothomes'. During the summer months tile and brick making doubtless involved the whole household. Writing of more recent times, an authority on country crafts says that 'while men and women undertook moulding, children were expected to supply the moulders with all the clay that they required and ensure that they had a plentiful supply of water and sand.(8) Coopery was probably Walton's winter occupation.

References

1 BRL 584315; Bickley Collection, VI, f.440; BRL 584333.

2 Inclosure award, 1847, Worcester Record Office, 307/75-f. 143/75.

3 BRL 584337.

4 BRL 426292; BRL 426293.

5 T.R. Nash, Collections for a History of Worcestershire (1781-99),II, p.478.

6 BRL 278094.

7 Worcester Record Office, 008.7/38/1554.

8 J.G. Jenkins, Traditional Country Craftsmen (1966), p.153.

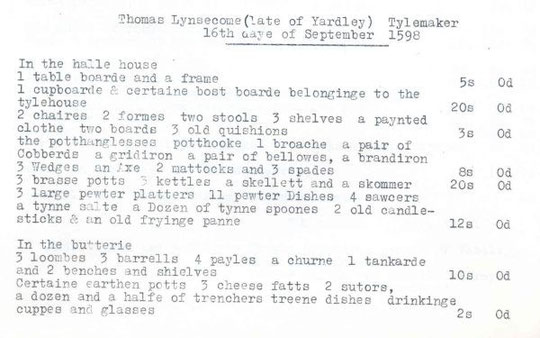

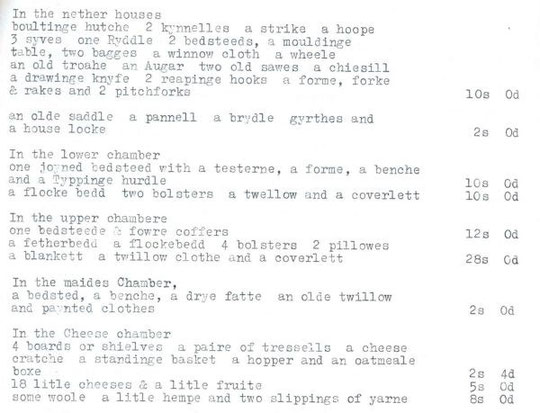

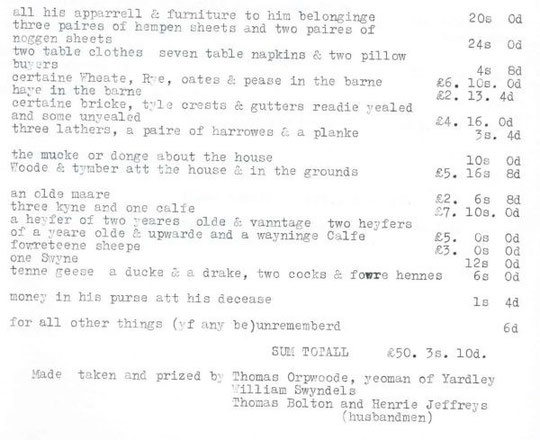

An inventory of 1598 listed crops to the value of £9 3s 4d, livestock to the value of £18 14s 8d, and bricks, tiles, and other building materials to the value of £10 12s 8d for Thomas Lynescombe (transcript by the Discovering Yardley Group).

Before urbanisation brick and tile making was a secondary occupation on local farms, with the farmers manufacturing themselves or renting out the land to others. The clay dug from the fields in the autumn would be left to weather and be turned over the winter, then it would be ground and mixed by being trod by foot or with a horse working a mill by walking round in a circle. Because of the need to dry the worked clay before it was fired, summer was the time for making bricks until steam power came in. Albert Stephenson published a book in 1933 on the Trade Associations of Birmingham Brick Masters, where he talked of the "old school of brickmakers, who often made bricks in the summer, and were maltsters and brewers in the winter". (page 98)

Proximity to Birmingham provided a growing market. Transport would have been difficult along rutted lanes and poor roads, though. After main road improvements and after the Birmingham and Warwick Canal came through Yardley (there were wharves at Tyseley and Acocks Green), the export market was easier to access. T.R. Nash (1799) wrote about Yardley thus:

Here is a considerable manufactory of burnt tiles for covering houses, consisting of 24 tile houses, each of which makes yearly at least 150,000 tiles. (page 478)

By the 1840s there were almost as many sites, but soon afterwards Welsh slate began to be transported via the railways, and tile making suffered competition. However, brickworks did flourish later in several places, initially serving the terrace building period. Some of these were large, for example the Burbury in Greet, and Derringtons and Bayliss's Waterloo Brickworks in Tyseley/Hay Mills.

Albert H. Stephenson bemoaned the low status of brick making in his book, and the inability of manufacturers to come together to prevent prices falling below cost. A meeting in November 1869 was attended by thirty-seven brick masters. Derringtons later provided a list of manufacturers of that time, among which were George Clark, Yardley; Bagnall, Lyndon Orchard (? Yardley); Joseph Kemp of Yardley; Joseph Payton of Yardley; David Shirley of Acocks Green; Henry Smith, Rushall Lane (later Stockfield Road), Acocks Green; and Thomas Williams of Newbridge, Yardley.

The Yardley Tithe Apportionment 1847 has references to brick, kiln and tile, which have been collated in the pages covering particular districts. These have been written in conjunction with Birmingham Libraries. Also, references in directories from 1841 and 1850 have been included in this section.

The Discovering Yardley Group's papers make other references around the same period. Their analysis of the 1841 census revealed two brick makers in Greet Quarter (between the Warwick and Coventry Roads) and one brick maker in "all that part of Yardley village, Stychford and New Bridge which lies north of the church". As regards tile makers, there was one in Greet Quarter, ten in "all that part of Yardley village which lies south of the church and north of the Coventry Road", and two in "all that part of Yardley village, Stychford and New bridge which lies north of the church".

The Discovering Yardley Group's analysis of the 1851 census shows one brick maker (journeyman) in Church Quarter (north of the Coventry Road), and four brick makers in Swanshurst Quarter (south of the Stratford Road). Three tile makers and four journeymen tile makers are in Church Quarter, one tile maker and five journeymen in Greet Quarter, and two tile makers in Broomhall Quarter (between the Stratford and Warwick Roads).

Directory listings are included on another page, which concentrate on the period to 1911. The page on Greet and Tyseley, and that on Hay Mills continue the story after that.

Brick and tile making in Yardley

Billesley, Hall Green and Acocks Green

Acocks Green History Society

Acocks Green History Society